Dongola (Sudan)

Polish Archaeological Mission in Dongola, 2013

Dates: 18 November 2012 – 19 December 2012

and 19 January 2013 – 16 February 2013

Cooperating institutions:

PCMA UW; Department of the Archaeology of Egypt and Nubia, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw; National Corporation of Antiquities and Museums, Sudan

Director: Prof. Włodzimierz Godlewski, archeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Team:

Katarzyna Danys–Lasek, archeologist/documentalist (freelance)

Lucia Dominici, volunteer (Italy), PhD candidate (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Justyna Dziubecka, student of archeology (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Łukasz Jarmużek, archeologist, PhD candidate (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Jolanta Kurzyńska, wall painting conservator (Academy of Fine Arts, Kraków)

Prof. Adam Łajtar, epigraphist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Dr. Marta Osypińska, archeozoologist (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poznań)

Marek Woźniak, archeologist, PhD candidate (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences)

Dr. Dobrochna Zielińska, archeologist (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw)

Ajab Said el-Ahmed, archeologist, inspector (NCAM)

Excavation and conservation work in 2012/2013 were carried out in the Citadel (royal building complex SWN, B.I and B.V), including the area of the northeastern defense tower, and Kom H (southwestern quarter of the monastery enclosure and Southwest Annex).

Citadel fortifications

The Dongolan citadel rises impressively over the ancient capital of the Nubian kingdom of Makuria, having been built in the 5th and 6th century on a rocky uplift along the Nile bank. The fortified space covered around 37.000 sq. m. Massive defense walls stood on the north and east: the curtain was 5.70 m wide, the tower projecting from the curtain 8.50–8.90 m. Mud brick and broken limestone were used for the outside face (approximately 0.90 m thick). The towers were set at regular intervals of 32–35 m. The northwestern tower, which had been explored partly in 1993–1995, still stands about 6 m high on a rock foundation. The riverside defenses were constructed of mud brick and measured 3.70 m in the northern part and 2.10 m in the southern part.

The northeastern tower, which was explored during the first campaign of the season, was in a much better state of preservation than the described northwestern tower [Fig. 1].

It was founded on bedrock, 9.00 m long, 6.10 m wide and 8.35 m high in its present state. A house from the 17th century village, which occupied the citadel, was erected on top of the tower ruins, using the stone remains as its outer walls. Taking this into account, the original height of the tower (and the curtain on either side of it) could be estimated at about 10.50–11.00 m.

Sometime in the end of the 16th century the fortifications were renovated and developed. Sand dunes accumulated against parts of the curtain were removed and a new outer facing of dried bricks added, approximately 1.00 m wide, on a level 4.70 m higher than the stone-wall foundation. The project appears to have been in response to a growing Ottoman threat (the excavator had previously suggested a date in the end of the 13th century, in defense against raiding Mamelukes). The pottery assemblage, which was recovered from sand corresponding stratigraphically to the dried-brick wall facing, was entirely handmade (not one sherd of wheel-made ceramics was found) and was undoubtedly post-Makurite in date. It could be attributed to the 15th–16th century. The dwellings to the north of the fortifications, excavated in the previous season of fieldwork, were dated to the 17th century [Fig. 2a,b].

These were small houses with no upper storey, built of dried brick, usually with two or three interiors, founded directly on the sand dune. A rich assemblage of handmade domestic pottery, attributed to the last phase of the functioning of the house and hence dated to the 17th century, was excavated in house DH.116 [Fig. 3].

The pots were finely burnished on the outside, decorated with bands of engraved decoration and a neatly impressed mat on the bottom part.

The sand fill by the northeastern tower, already below the foundation level of the dried-brick curtain facade, but also corresponding to and above the foundation, yielded an extensive assemblage of faunal remains. The bones were evidently post-consumption refuse dumped from the 17th century village located on the citadel summit. Archaeozoological research has established that villagers in the 17th century were eating mainly cattle and camel meat. Archaeozoologist Marta Osypińska identified also sheep and goats, dogs as well as a few horses and pearl oyster.

Royal architecture on the citadel (SWN, B.I and B.V)

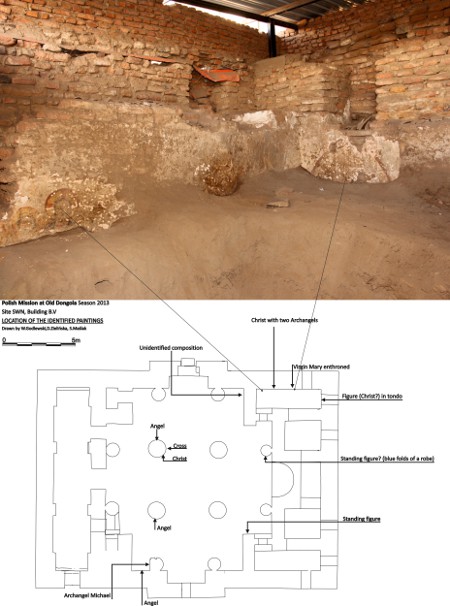

Excavations of the palace of King Ioannes (end of 6th century) and a large church (B.V) to the south of the palace have continued for the past few seasons of fieldwork. The church B.V was a large central basilica (25 m by 15 m). In previous seasons the ruins, which stand to a height of more than 4.00 m in the eastern and southern parts, were covered with a metal shelter roof and screened off from tourists [Fig. 4].

The interior is now being gradually emptied of sand, allowing the conservation of the murals preserved on the lime-plastered walls to proceed at its own pace, determined by conservation needs [Fig. 5 a,b].

Unfortunately, the plaster and the murals are severely damaged. The church appears to have been connected with the palace of Ioannes, but was a much later foundation than the royal residence, having been constructed most probably in the 9th century (a more precise dating will have to wait for the excavations to be completed). Building features suggest that it was one of the best architectural achievements in Dongola and the quality of the murals as well as the lime plaster ground are of the highest mark.

The paintings bear legends in Greek, but there are also some inscriptions in Old Nubian, which would have been added presumably at a later date.

Three trenches were explored inside the palace building (B.I), one in the eastern part and two in the western one. Trench 2013.01, traced on the E–W axis of the structure at its eastern end, reached the tops of walls of the palace ground floor, about 3.70 m above walking level in the western part of the structure (the ground floor in this part of the building is known to have measured more than 4.00 m in height). In the western part of the trench, the walls of the original palace appear to rise beyond the ground floor [Fig. 6]. It is too early to ascertain beyond all doubt that this was the eastern facade of the building. The upper layers in the trench revealed ruins of 16th–17th century village architecture [Fig. 7].

In the two western trenches, 2013.2 (B.I.11) and 2013.2 (B.I.36), the destruction layers from the end of the 13th century were removed, revealing palace wall foundations superimposed on remains of earlier architecture. This building (B.X), preceding the palace of Ioannes, was a dried-brick structure lined up with the western defense wall, located approximately 1.80 m away from it.

It formed part of a complex of architecture already recorded in other trenches: a structure in front of the southern palace facade (Building B.IV), made of red brick and furnished with a red-brick floor, and dwelling H.111, discovered in the northwestern corner of the citadel, under the foundations of house H.106 built of dried-brick. Pottery found in the foundations of B.X and H.111 is dated to the middle of the 6th century or earlier.

Southwestern courtyard of the Monastery on Kom H

The southwestern quarter of the monastic enclosure on Kom H, including the outer annexes to the north of the western gate, was explored in the course of the season. This part of the compound comprised a courtyard, which opened from the western gate and which extended in front of the west end of the church and the adjacent sanctuary of Anna By. An inner enclosure wall partitioned off this open space from the rest of the monastery inhabited by the monks [Fig. 8]. It was intended presumably for lay visitors to the monastery, presumably coming to the sanctuary of Anna By, who would have entered the complex through the western gate, which led from the direction of the town. A red-brick pavement fronted the entrance to the church and the south side of the sanctuary. The outer enclosure wall of the monastery in this sector was constructed of dried brick and was about 1.30 m wide. The southwestern corner was reinforced with a semicircular tower that was accessible through a door in the wall. This tower appears to have served as a place for preparing meals for the visitors to the monastery.

Two phases of architectural development were identified in the construction of the western gate to the monastery. In its initial form it was an entry in the wall, approximately 1.75 m wide, with two inner antae walls, each a meter wide. The walls next to the entrance on the outside and in the passages were faced with red brick. The jambs in the entrance, by the west face of the wall, were made of sandstone blocks; some fragments of the northern jamb have been preserved, but the southwestern corner was entirely dismantled at some point.

The second phase of the gate revolved around a semicircular tower being added in front of the entrance on the outside. The feature was 6.20 m wide and 5.80 m long, and was entered from the south. The walls, made of dried brick, were 1.10 m thick. A small unit with a floor of ceramic tiles was installed inside the tower, by its west wall. The southern door, which had a maximal width of 1.60 m, had jambs faced with red brick and a threshold of granite; only the east jamb has been preserved along with one slab from the threshold, but the west jamb can be presumed to have been the same. The entrance passage was just 2 m away from the face of the corner tower of the monastery enclosure [Fig. 9].

Building WH.1 (Southwest Annex) of the monastery

Work in the southwestern quarter of the monastery involved also a comprehensive review of the excavated sections of outside annexes added to the west wall of the monastic compound, immediately to the north of the west gate. This presumably storied building extended from the west gate to the north, in the direction of another annex built earlier along the outside of the monastery wall (Building WH.2 = Northwest Annex). The structure had been excavated first by Bogdan Żurawski in 1995 and again by Stefan Jakobielski in 2005; the wall paintings from the annex were published recently by Małgorzata Martens-Czarnecka (2012). The poor condition of the shelter roof constructed in 2005 called for immediate action and a new metal roof was installed this season.

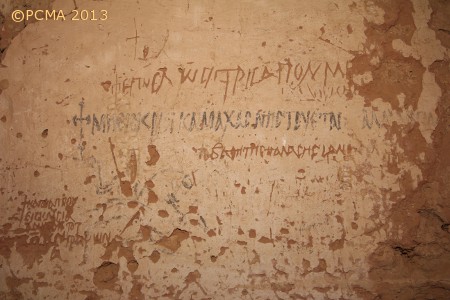

The work provided an opportunity to clear the west facade of accumulated sand [Fig. 10], as well as to carry out additional research and documentation of the architecture, paintings and inscriptions preserved on the walls. Studies undertaken by Adam Łajtar on the inscriptions from Building WH.1 have demonstrated that most of them were written in Greek. Only a few of the graffiti scratched in the plaster were in Old Nubian [Fig. 11]. Most of the Greek texts were legends accompanying murals — prayers and literary texts (psalms); despite their poor state of preservation, they are of key importance for understanding the repertoire of painted decoration on the ground-floor of the structure. The graffiti were left by visitors. None of the inscriptions included a date.

The building was undoubtedly of a religious character, but the exact function has not been determined despite the preserved inscriptions and murals, as well as some inner installations. Neither has the founding date of this structure been established, although the building is evidently later than the second architectural phase of the west gate. The annex was open to visitors from outside the monastery, but the staircase installed in one of the southern units of the annex permitted inner communication not only with a presumed upper floor, but also with the monastic buildings beyond the monastery wall.

[Text: W. Godlewski]